CSI, ECU Researchers Study Beach Nourishment Effects on Pea Island

The Outer Banks has seen beach nourishment projects as recently as 2019 in Nags Head. [Photo courtesy Town of Nags Head.]

Corbett and Paris study the PINWR 2014 beach nourishment as the main focus of their ongoing research. To the left, progress is made in pumping sand on to the beach just north of Rodanthe in 2014. [Photo courtesy of Hyunsoo Leo Kim, The Virginian-Pilot.]

Corbett, along with Spencer Wilkinson and Anya Leach, prep for a day of field work at PINWR.

Researchers stand in swash zone as they look for organisms within their sample.

Over the course of this new study, Corbett and Paris are seeking to understand the longer-term effects of the 2014 nourishment project. To do so, they and their research team will collect data from the field surveys and take sand samples back to the lab to be processed. In addition to collecting sand samples on the beach, they will randomly select small plots near sand collection sites to estimate the presence and abundance of ghost crabs. In the swash zone, they will also collect, assess, and then release live samples to be sieved and counted for all macro-organisms which could include mole crabs, coquina, amphipods, and polychaete worms. Beach geomorphology, including the elevation and slope of the beach, will also be recorded using a field GPS device. Other on-site measures will also be conducted, including, but not limited to sediment compaction, tide stage, and air and water temperature. In the lab, the researchers will analyze the sand grain size and heavy mineral content.

Tiny coquina are among the samples taken, processed, and returned from the swash zone.

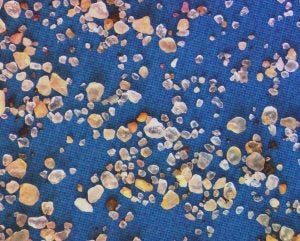

Once back in the lab, sand content analysis can begin. Pictured are many different grain sizes before being further separated.

The data mentioned above, combined with USFWS records for sea turtle and shorebird nesting populations, will help the researchers to record the long-term effects of a beach nourishment project. Corbett elaborates, “We are interested in the possible influence of nourishment on physical aspects of the beach, as well as long-term biological changes. Changes in grain size can influence the “critters” living in the surf zone which might impact foraging birds, while changes in beach slope may alter sea turtle nesting.” Up to this point, studies were short-term and did not extend the estimated lifespan of a typical beach nourishment project which is usually 5-10 years. The ongoing study conducted by Corbett and Paris will end with results that rest within the 5 to 10-year threshold. Hopefully, their study will yield more conclusive results and shed light on the uncertainty associated with such projects regarding their physical and biotic affects. The study also has the potential to inform future municipal and environmental management decisions. Corbett believes PINWR is an exemplary study site, stating there “aren’t many places around the world where there is little anthropogenic [human-induced] change to the beach except a single nourishment. The PINWR is really unique and offers a great place to study the impact of nourishment.”

Corbett and Paris expect their study to wrap-up in Fall 2021, and members of the public can anticipate learning more in the meantime at an upcoming Science on the Sound lecture at CSI in Fall 2020 or Spring 2021.