Land Conversion and Shoreline Erosion Battle for the Largest Contribution of Mangrove Loss

Dr. David Lagomasino

Dr. David Lagomasino, an ECU Department of Coastal Studies Assistant Professor and Assistant Scientist at CSI, has co-authored a recently published paper, “Global declines in human driven mangrove loss”, in the scientific journal Global Change Biology.

Lagomasino, working alongside the lead author of the paper Liza Goldberg and two others from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, used a machine-based learning approach to produce land cover maps from over one million NASA Earth observing satellite images. The resulting high-resolution maps were used to analyze worldwide mangrove loss from 2000 to 2016. Prior to their study, the distribution and trends of natural and anthropogenic, or human-caused, drivers of mangrove loss had not been fully quantified on a global scale in an actionable way needed for policy, conservation, and restoration efforts.

Within the research findings, the team reports that 62% of global mangrove loss since the beginning of the 21st century has resulted from human land-use change. Of those losses, 47% were a result of agriculture and mariculture practices like rice paddies, shrimp ponds, and palm oil cultivation; and nearly 80% of human-driven losses occurred within six Southeast Asian countries. While anthropogenic causes of mangrove loss are extremely prevalent in those countries, human-driven mangrove loss has declined by 73% worldwide. “These declines we see could be a result of better farming practices, mangrove conservations, policy changes, or the loss of suitable farming lands”, Lagomasino states. However, that is not to say that mangrove threats are disappearing altogether.

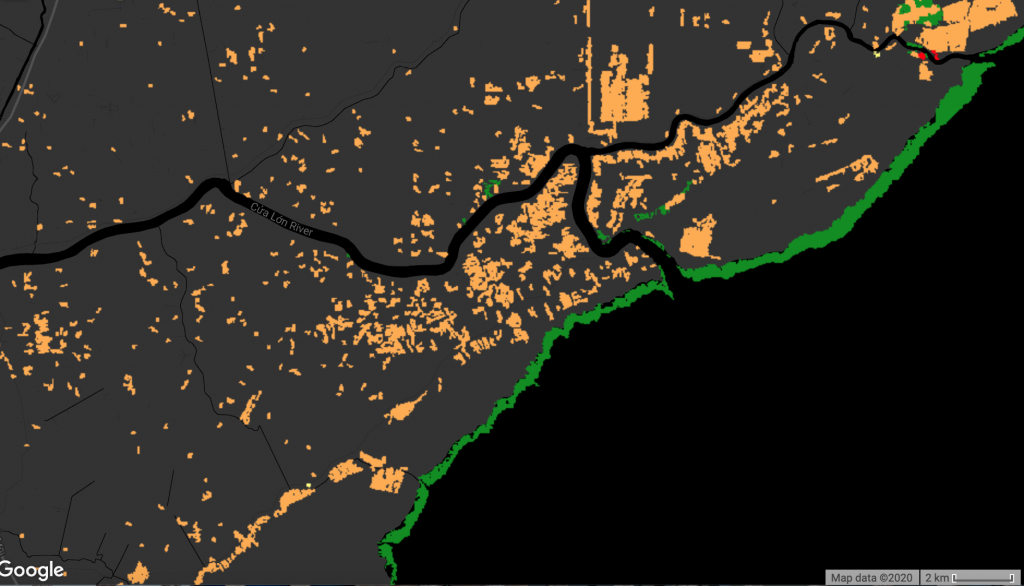

This map of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam indicates that commodities (orange) and erosion (green) are the two largest drivers of loss for this area during the 21st century.

In almost all of the countries in which mangroves are found, natural phenomena such as shoreline erosion and extreme weather events, like hurricanes and droughts, also contribute to mangrove loss. During the study period, total mangrove loss area declined; however, the relative impact of natural drivers on mangrove loss actually increased by nearly 10-20% depending on the area over the 16-year period. Excluding the six Southeast Asian countries mentioned previously, erosion caused nearly half (~43%) of mangrove loss around the world from 2000-2016, and extreme weather events drove between 18-22% of total mangrove loss area on each continent. Lagomasino adds, “The differences we see in the relative contribution of natural and human-derived mangrove loss shows us the large influence humans have on the coastal environment. Identifying where and when these changes are happening is a step toward developing region-specific coastal mitigation strategies.”

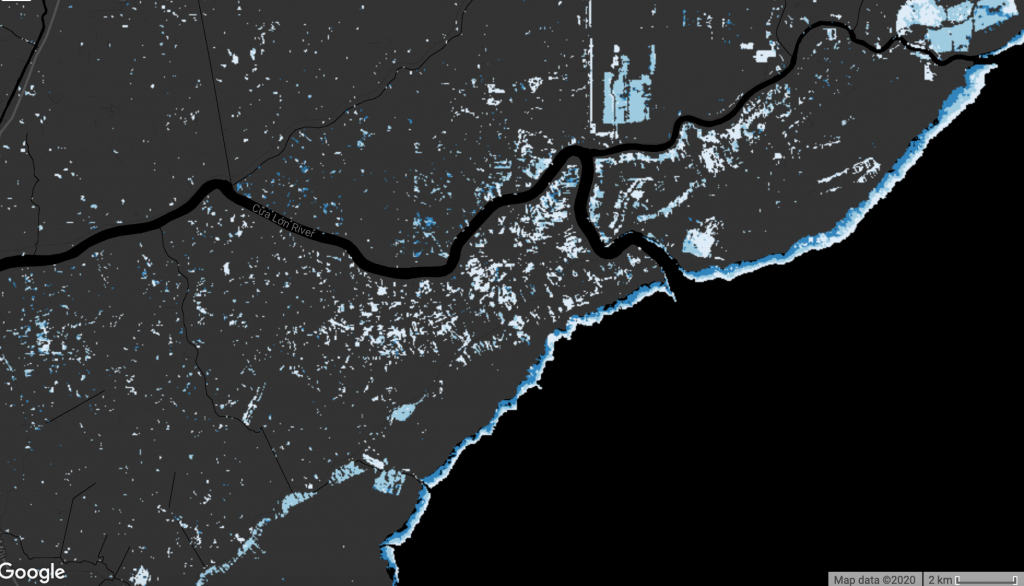

This second map of the same area indicates the loss of mangroves over time. Loss is show in five year increments: 2000-2005 (light blue), 2005-2010 (medium blue), and 2010-2015 (dark blue).

While an overall decline in mangrove loss was observed from 2000-2016, it is important to continue to recognize the value of land-use management and conservation. Naturally-driven losses will continue to compound the impacts of previous mangrove loss from both natural and anthropogenic sources – particularly in areas where mangroves are barred from expanding landward. The authors suggest that future conservation policy should plan for natural stressors from extreme weather events and oceanic processes which will continue to squeeze mangroves between the ocean and human development. In the paper they state, “Regardless of the current level of direct human intervention in the forest, the intersection of existing anthropogenic and future climate losses must be considered when enacting future ecosystem valuation and conservation on an increasingly human-dominated planet.” Mangroves are an important ecosystem for protecting shorelines and offsetting carbon and thus a great natural tool for combatting extreme weather and a changing climate.

Of special note for this paper, lead author Liza Goldberg just graduated high school and was a former intern of Lagomasino’s. To read more about Goldberg’s experiences with the project and NASA Goddard internship, click here; and to visit the Drivers of Global Mangrove Loss website or to read the paper, click here.